| This is how your last three seconds could look to an F-16 pilot. |

We could just give up and rely on the "Big Sky - Little Airplane" theory of

collision avoidance, but maybe there are some things we can do to improve our

chances of success. One is to know where traffic is more likely to be and avoid

those areas when it is reasonable to do so. If it is not, then at least exercise

extra caution. Some of the places where airplanes are more likely to be include,

airports and airways for civilian aircraft and special use airspace and Military

Training Routes for military aircraft. In the following table we show examples

of these along with some of the restrictions and precautions related to their

use.

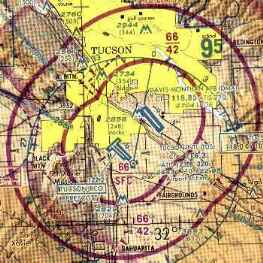

Class B airspace is the most restrictive for glider pilots, and is

usually the most complex. In this partial view of PHX you can see the different

shapes and altitudes of different segments. Entry requires a clearance (ergo

two-way communication) and a Mode C transponder with altitude encoding. Gliders

are exempt from the Mode C requirement within the 30 NM Mode C Veil, but not

within Class B airspace nor above it to 10,000 feet MSL.

Class B airspace is the most restrictive for glider pilots, and is

usually the most complex. In this partial view of PHX you can see the different

shapes and altitudes of different segments. Entry requires a clearance (ergo

two-way communication) and a Mode C transponder with altitude encoding. Gliders

are exempt from the Mode C requirement within the 30 NM Mode C Veil, but not

within Class B airspace nor above it to 10,000 feet MSL.

Perhaps the most serious collision risk for gliders

operating near busy commercial airports involves airplanes descending to

the airport on Arrival Routes. A collision involving a glider and an air

carrier would likely be fatal to the sport of soaring as well as the

people involved. Arrival Routes are not shown on any charts normally used

by glider pilots except for the symbol shown here from an Area chart. Perhaps the most serious collision risk for gliders

operating near busy commercial airports involves airplanes descending to

the airport on Arrival Routes. A collision involving a glider and an air

carrier would likely be fatal to the sport of soaring as well as the

people involved. Arrival Routes are not shown on any charts normally used

by glider pilots except for the symbol shown here from an Area chart.

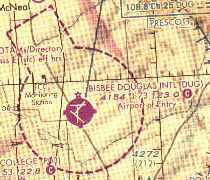

|  From the glider pilot's perspective, Class C is not

significantly different from Class B. Two-way communication is required

for entry, but not specifically a "clearance", and Mode C transponder with

altitude encoding is required in and above Class C up to 10,000 feet MSL.

This illustration shows two overlapping Class C areas. From the glider pilot's perspective, Class C is not

significantly different from Class B. Two-way communication is required

for entry, but not specifically a "clearance", and Mode C transponder with

altitude encoding is required in and above Class C up to 10,000 feet MSL.

This illustration shows two overlapping Class C areas. |

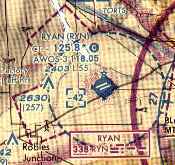

Two-way communication is normally required for entry

into Class D airspace. The Aeronautical Information Manual recommends the

initial call be made 15 miles out. The tower frequency is shown on the

chart after the letters "CT". Class D airspace usually extends from the

surface to 2,500 feet AGL, but in this case overlying airspace restricts

the top to 4,200 feet MSL, shown in the small box as "-42". Two-way communication is normally required for entry

into Class D airspace. The Aeronautical Information Manual recommends the

initial call be made 15 miles out. The tower frequency is shown on the

chart after the letters "CT". Class D airspace usually extends from the

surface to 2,500 feet AGL, but in this case overlying airspace restricts

the top to 4,200 feet MSL, shown in the small box as "-42".

|  Communication is not required for operations in

Class E airspace, but the Aeronautical Information Manual recommends

"self-announcing" to other traffic 10 miles out and entering downwind,

base and final when landing at a non-tower airport. The common traffic

advisory frequency, CTAF, is indicated on the chart by the letter "C"

enclosed in a solid colored circle. Communication is not required for operations in

Class E airspace, but the Aeronautical Information Manual recommends

"self-announcing" to other traffic 10 miles out and entering downwind,

base and final when landing at a non-tower airport. The common traffic

advisory frequency, CTAF, is indicated on the chart by the letter "C"

enclosed in a solid colored circle. |

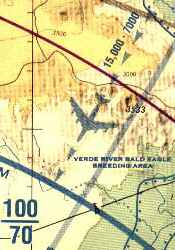

Victor Airways, V-16 in this illustration, are shown

in blue on aeronautical charts. They are based on VOR navigation

facilities, and are used primarily by general aviation pilots. Military

Training Routes (MTRs) are shown in gray, with the letters "VR" or "IR",

indicating visual or instrument routes, followed by the route number.

Glider pilots should be alert for high speed military aircraft along these

routes. Planned activity can be obtained from Flight Service. Victor Airways, V-16 in this illustration, are shown

in blue on aeronautical charts. They are based on VOR navigation

facilities, and are used primarily by general aviation pilots. Military

Training Routes (MTRs) are shown in gray, with the letters "VR" or "IR",

indicating visual or instrument routes, followed by the route number.

Glider pilots should be alert for high speed military aircraft along these

routes. Planned activity can be obtained from Flight Service.

|

Military Operations Areas (MOAs) have a magenta crosshatched border. Information about their times of use and the applicable altitudes can be found on the border of the chart. No clearance is necessary for operation in MOAs, but glider pilots should exercise caution when the area is active. |

Restricted Areas, shown on charts with a blue

crosshatched border, require a clearance to enter during times of use.

Times and altitudes are shown on the chart border, along with the

controlling agency. It will usually be easier for glider pilots to obtain

information about restricted areas by contacting Flight Service. Restricted Areas, shown on charts with a blue

crosshatched border, require a clearance to enter during times of use.

Times and altitudes are shown on the chart border, along with the

controlling agency. It will usually be easier for glider pilots to obtain

information about restricted areas by contacting Flight Service.

|

Alert Areas are also depicted with blue crosshatched borders. That is difficult to see in this illustration because most of the Alert Area's border coincides with the magenta boundary of Class E airspace beginning at 700 feet AGL. Alert Areas, like MOAs, require no clearance, but extra caution is advised. |

FAR 61.89 further restricts Student Pilots to three mile visibility during

the day and five miles at night. FAR 91.155 has a couple of exceptions for

airplane and helicopter pilots but none for gliders.

Return to: Top 10 ways to fail your checkride...